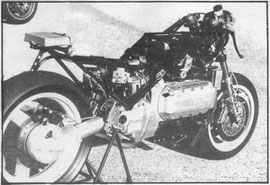

No hay dos sin tres: la JJCobas BMW 1000cc

El proyecto BMW fascinó a Antonio des de los primeros momentos. A Antonio le

gustava aplicarse para hallar soluciones a problemas de dificil solucion , y hacer de la K-100 una moto de carreras era un problema suficiente para volver loco a muchos.

MV Augusta intentó brevemente hacer de la 750 América una Formula 750 para Agustini, pero despues de la paliza que Ducati les dio en Imola en aquella famosa carrera ganada por Paul Smart, MV

Augusta tiró la toalla. Más tarde, Laverda intentó correr con la V-6 de transmision por cardan, pero al chocar contra el problema clásico de la “cruceta” o junta cardánica entre el eje conductor

y el eje conducido ellos tambien tiraron la toalla.

El problema, explicadó de forma sencilla, es la aliniacion del eje conductor

y del eje conducido. Cuando el basculante actua, los ejes quedan desaliniados, se alteran los ciclos de transmision y ya no es uniforme la fuerza transmitida a la rueda, puesto que los dos ejes

no giran en la misma velocidad.

La consecuencia inmediata de estas desaliniaciones es una serie de rebotes, saltos, vibraciones y fenómenos de resonancia que hacian extraña de conducir la moto. Para minimizar estas diferencias

de velocidad entre los ejes, es preciso limitar el recorrido útil de la suspension trasera, y asi, a pesar de haber aplicado una suspension de progresividad variable, el recorrido era menos que

óptimo.... unos 125 mm.

A.Cobas explicó que los neumaticos de competicion de 1984 tenian una frecuencias de deformacion que requerian inevitablemente suspensiones de largo

recorrido .” Los Slicks normales para carreras no servian para esta moto y tuvimos que buscar slicks raros de perfil alto” estos

neumaticos se parecian más a los que calzaba la MV Augusta de Phil Read en el 74 a los que se montavan en el año 84.

Otro problema directamente relacionado con los rebotes y fenómenos de resonancia es el incremento de pesos no suspendidos del sistema por cardan, en comparación con el de una transmisión

secundaria por cadena.

“Hasta aquel momento”, dijo Antonio,” nadie quiso enfrentarse con estos

problemas en el campo de la moto, pero en el sector del automóvil si y yo me he puesto en contacto con Hardy Spicer, el mejor especialista en juntas homocinéticas para intentar a largo plazo

conseguir juntas homocinéticas para la BMW.”

La junta homocinética garantiza que las velocidades de los ejes siempre sean equivalentes y la mayor investigacion en este campo se produjo cuando los coches de Formula 1 empezaron a utilizar

frenos “inboard” montados sobre el eje de salida del diferencial en lugar de en las ruedas. La idea era reducir el peso no suspendido, pero al montar los frenos “inboard” tuvieron que hacer mas

cortos los semiejes de transmision, cuya funcion es equivalente a la del eje conducido (el que pasa por el interior del basculante), y esto aumentava las variaciones del angulo de ataque sobre el

eje conductor. Como no podian darse el lujo de sacrificar recorrido de suspension, tuvieron que enfrentarse con el problema basico.. y de esta investigacion nacieron las juntas

homocinéticas.

“La junta homocinética es totalmente inprescindible para una moto de carreras con cárdan”, explicó Antonio. “Es la única manera

de poder utilizar una suspension de largo recorrido, neumaticos normales y la única manera de reducir fenómenos de resonancia, saltos, etc.”

LA ELECTRONICA.

Pero con los compromisos de una suspension de recorrido corto y unos neumaticos “raros” que se parecian a los antiguos SB-15, la JJ-BMW

funcionava tan bien y era tan agradable y facil de conducir que no era descabellado soñar con una victoria en su gran debut en Montjuïc.

Aquel debut, sin embargo, pronto dejó de ser un sueño, para convertirse en una pesadilla. Posiblemente el exceso de celo en dibulgar algunas de las “peculiaridades” de la electronica de los

motores K, por parte de Bosch y BMW, al no facilitar esta informacion vital al equipo de Eduardo Giro, el resultado podria haver sido otro a tenor de los resultados obtenidos por esta maquina una

vez “solucionados” los problemas con la electronica.

En tandas de 10 y 20 vueltas en Calafat, la moto funcionava perfectamente. Pero en Montjuïc la moto sufrio una serie de fallos eléctricos que acabaron con las esperanzas del equipo....y por poco

con Quique de Juan que acabo herniandose mientras empujaba la moto en la subida de San Jorge ...¡ en dos ocasiones!.

“En primer lugar las vibraciones de la “K” eran vibraciones horizontales y nosotros teniamos las cajas

electronicas de la inyeccion montados verticales. Despues de 27-30 vueltas en Montjuïc la caja marcaba ¡tilt!. Los circuitos de proteccion se bloquearon, apagaron la maquina y para jugar habia

que “meter” otro “duro”: O sea que tuvimos que quitar la caja, poner otra, y a rodar otras 20 o 30 vueltas. Pero despues pudimos volver a montar las mismas cajas de antes, puesto que...despues de

un periodo de reposo, recuperaban todas las facultades”.

También habia problemas de distribucion de ramales, se producian campos magnéticos y los circuitos de proteccion volvieron a bloquearse.

“Otro problema de indole electrónico era el limitador de vueltas, programado para modificar

progresivamente el avance a alto regimen cortando el encendido definitivamente a 8.640 rpm.

Con nuestros arboles de levas y escapes preparados queriamos girar a 9.200 rpm y para hacerlo tuvimos que “engañar” al limitador, robandole informacion, haciendo puentes para saltar el limitador,

y volviendo a reintroducir la informacion por otros conductos.”

Despues de las 24 horas, explicó Antonio, unos señores de BMW y Bosch les facilitaron suficiente informacion para permitir al equipo de Giró (trabajando conjuntamente con la compañia de

ingenieria electrónica Analec) trabajar durante dos meses en banco de pruebas, solucionando por fin todo este complejo de problemas electónicos. Y en las seis mangas de formula 1 que restaban de

las Motociclismo Series, Carlos Cardus con la BMW JJ COBAS fue intocable, sin que se produjera el más mínimo fallo.

El Motor

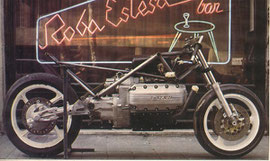

“El motor, como propulsor, entra en el campo de Eduardo

Giró, pero en esta moto, el motor es pieza fundamental del chasis. Es la primera vez que he podido trabajar con un verdadero motor portante”. Este era el comentario que Antonio hizo sobre el

motor de la moto... y prosigue “ Por ser un motor de carrera larga (diametro 67 mm y carrera 70 mm) es imposible conseguir los regimes de giro

necesarios para obtener potencias muy altas. Si intentamos hacer girar el motor a alto regimen nos meteriamos en problemas de velocidad linial del piston.” “Pero por otro lado, hacerlo “cuadrado”

o “supercuadrado” reduciendo la carrera y aumentando el diametro supondria hacer un motor 3 o 4 cm más largo...y esta moto ya es de por sí bastante larga”.

Para llevar el motor de la “K” a essos 122 CV que rendia la moto a 9200 rpm tuvieron que modificar la curva de avance , “engañar” el limitador de vueltas y conseguir una carburacion ideal con los

nuevos arboles de levas y el nuevo escape “cuatro en uno”.

Si se extrae una bujia y se observa que la mezcla va fina, con una moto equipada con carburadores normales, sabremos siempre qué hacer, pero con la inyeccion no hay chiclés intercanviables.

Cuando consideras todos los los problemas que Giró ha tenidó que afrontar para sacar potencia del motor “K” te das cuenta de que conseguir un motor que da 80 CV a 6000 rpm y 122 CV a 9.200 rpm

representa una hazaña importante.

La “K” de serie monta válvulas grandes, tan grandes que es imposible meter otras válvulas más grandes. “Con válvulas tan grandes seria muy

dificil trabajar con carburadores, porque la enorme área de las valvulas de admision reduciría la succion del cilindro a bajo regimen”.

Dice Cobas. Asi, la inyección electrónica, a pesar de todos los inconvenientes, se antoja ideal para la BMW. “Creemos que el techo de este

motor está en los 130 CV. En la recta del Jarama corre más que nuestra JJ Cobas 250CC y calculamos una velocidad máxima de unos 255 KM/H.”

No són cifras muy altas para una Formula 1 de 1000 CC, pero la gracia de la BMW esta en su estabilidad y la docilidad de su motor. Los 80CV a tan solo 6000 rpm le permiten “ducatear” en marchas

largas con una tetacilindrica de 178 kilos, descansando la mecanica y el piloto, factor muy importante en resistencia.

English version: The JJCobas BMW

All good things come in threes: the JJCobas 1000cc BMW

Antonio was captivated by the BMW project from the very beginning. Antonio liked to find

solutions to tricky problems, and transforming the K-100 into a racing bike was a problem big

enough that would scare many.

MV Augusta briefly tried to transform the 750cc América into a 750cc Formula for Agustini.

However, they threw in the towel after getting crushed by Ducati in that famous race won by

Paul Smart in Imola. Later, Laverda tried to race with the U-joint V-6. But they had to give up as well, after running into the classic problem of the crosshead between the drive shaft and the lay shaft.

Explained simply, the problem was the alignment of the drive shaft and the lay shaft. When the swing-arm operates, the shafts go out of alignment and the transmission cycles are altered. This way, the power transmitted to the wheel is no longer uniform because the two shafts do not rotate at the same speed.

The immediate consequences are rebounds, jumpiness, vibrations, and resonance that make

the driving strange. To minimize the variation of speeds between the shafts, it is necessary to

limit the effective travel of the rear suspension. And despite using a suspension with variable

flexibility, the effective travel at 125mm wasn’t optimal.

A. Cobas explained that the race tires used in 1984 deformed easily, so they required long-

stroke suspensions. ‘The common racing slicks didn’t work for this bike and we had to find rare high-profile slicks’. These tires weren’t like those used in 1984, they were rather like those used on Phil Reads’ MV Augusta from 1974.

Another problem was that the U-joint system was heavier than a chain drive system, which also increased the rebound and resonance.

Antonio said ‘Until then, no one had wanted to face these problems in the motorcycle field, but they already did in the automobile sector. I have contacted Hardy Spicer, the best specialist in constant-velocity joints, to get them for the BMW on the long term.’

The CV joints guarantee equal speeds of the shafts. The greatest research on this field was

carried out when Formula 1 cars started to use inboard brakes, which were mounted on the

differential instead of the wheels. The idea was to reduce the unsprung weight. However, when placing the inboard brakes, they had to use shorter shafts. Its purpose is similar to the lay shaft, which goes through the inside of the swing-arm. Shorter shafts increased the angle of attack on the drive shaft. Since they couldn’t afford to reduce the suspension travel, they had to deal with the basic problem. That’s how they invented CV joints.

‘CV joints are essential for a U-joint racing bike with. It’s the only way to be able to use long-

stroke suspensions, normal tires and also reducing resonance, bouncing, etc.’, explained

Antonio.

ELECTRONICS

The JJ-BMW worked so well and was so nice and easy to drive with the compromises of short-

stroke suspensions and rare tires –similar to the old SB-15–, that they were dreaming to win its debut in Montjuïc.

However, the debut soon ceased to be a dream to become a nightmare. BMW and Bosch were reluctant to share some characteristics of the K engines’ electronics. The result could have been better if they had shared this information with Eduardo Giró’s team, as proven by the different results when the electronic problems were finally solved.

In series of 10 and 20 laps in Calafat, the bike worked perfectly. In Montjuïc, however, the bike experienced several electrical failures that ended with the team’s hopes. And it almost ended with Quique de Juan too, who gave himself a hernia while pushing the bike up the San Jorge hill (twice!) ‘First, K’s vibrations were horizontal, and we had mounted the injection system’s boxes vertically. After 27-30 laps in Montjuïc, the box was making a noise. The protection circuits were blocked and they turned off the bike. To buy time, we had to toss another coin. We had to remove the box, replace it, and drive another 20 or 30 laps. After that, we were able to place the same boxes back. After some rest, they worked normally again.

The distribution of the branch circuit had problems as well. It produced magnetic fields and the protection circuits were blocked again.

‘Another electrical problem was the rev limiter, which was programmed to progressively modify ignition timing at high speed by cutting the ignition permanently at 8,640rpm.

We wanted the rotational speed to be 9,200rpm, with our camshafts and exhausts prepared. To do so, we had to ‘trick’ the limiter: we removed information and made circuit bridges to skip the limiter and we re-entered the information through other channels.’

As Antonio explained: ‘After the 24-hours, some men from BMW and Bosch provided them with enough information to allow Giró’s team (together with the electronic engineering company Analec) to work on a test bench for two months, finally solving all these electronic problems.

Carlos Cardús with the BMW JJCobas was unbeatable for the remaining six laps of Formula 1

in the Motociclismo Series, without the slightest failure.

THE ENGINE

‘The engine was Eduardo Giró’s field, but in this bike, it is an essential part of the frame. This is the first time I’ve been able to work with a true load-bearing engine.’ This was Antonio’s

comment on the engine of the bike. It follows: ‘As it is a long-stroke engine (diameter 67mm and stroke 70mm), it’s impossibles to achieve the needed rotational speed to achieve high powers.

On one hand, if we try to achieve a high rotational speed, we will find linear velocity problems in the valve. But, on the other hand, making a square or over-square engine –reducing stroke and increasing the diameter– would require 3cm or 4cm more, and this bike is already quite long.’

To achieve the 122HP that the bike achieved at 9200rpm, they had to modify the timing curve,

to trick the restrictor and to achieve ideal carburation with the new camshafts and the new

exhaust four in one.

In a bike with common carburetors, we will always know what to do by removing the spark plug and checking if the blend is smooth. But with the fuel injection, there are no compatible jets.

If we take in account all the problems that Giró faced to get power from the K engine, you

realize how difficult it is to achieve an 80HP engine with 6000rpm and a 122HP engine with

9200rpm.

The standard K had large valves, so large that it is impossible to fit other larger valves. ‘With

valves this large, it would be very difficult to work with carburetors, because the huge space that the intake valves take up would reduce the cylinder suction to low revs.’,

says Cobas. ‘That’s why electronic injection, despite all the drawbacks, is ideal for the BMW.

We believe the limit of this engine is 130HP.’ In Jarama’s straight, it is faster than our 250cc

JJCobas and we estimate the highest speed at 255kmph (around 160mph).

It’s not a very high speed for a 1000cc Formula 1, but the BMW’S gifts are its stability and the

engine’s workability. The 80HP at only 6000rpm allows to ducatear* in high gear with a 178 kg

(390lbs) four-cylinder bike. This allows the driver and the mechanics to rest, which is very

important in the endurance side.

*ducatear is an invented verb used by Spanish motorbikes enthusiasts that means ‘driving

smoothly’. It refers to the Ducati brand, but it is used to refer to any bike.